Breaking Rank by Breaking the Line (Flip-Flop Flilosophy)

Everyone knows that a thru-hike is done by following a long trail continuously from end to end, and that there could be no other way, right? (Those most stuck in this mindset might also insist that northbound is the only possible direction…’NOBO or NOGOs’ may want to just stop reading here since the PNT is an east-west trail, which might be too mind-blowing:) Admittedly, a continuous line is usually the most logistically-easy and strategic plan, but also the most instinctual and traditional. Such journeys have their roots in religious pilgrimages, where the whole point is walking an unbroken path to arrive a place of significance, hopefully finding enlightenment along the way. A foot journey is also synonymous with epic stories like the Lord of the Rings. Frodo had to take the ring from the safety of the Shire to the depths and despair of Mordor because it was the only way. Even in nature, large-scale migrations generally unfold in a linear fashion. An arctic tern flies from one pole to the other, not halfway to jump a train to reset, then fly the other way. Thus, flip-floping kind of goes against the very core of our innate and romanticized ideals of thru-hiking.

But when we consider that most long-distance trails are basically arbitrary human constructs, it might become more palatable to let go of hang-ups over direction and the breaking of footsteps. The PNT was my 10th long distance hike, so I came to it with a more relaxed and flexible vision, gained from many thousands of ‘wrong-way’ miles. I’ve been pretty open-minded in my approach to thru-hiking from early on, beginning with my SOBO PCT thru-hike. I was coming off the heels of SOBO hikes of the Colorado Trail and Te Araroa, so it already seemed like a logical option. But more decisively, the winter/spring-season of the TA dictated my later start on the PCT…perfect for a SOBO. I found that I loved going against the grain, then again on the CDT and AT. Even still, I wanted to try new things, so I added a small flip-flop to the CDT. I hiked part of New Mexico NOBO in the spring (enjoying better water sources and the desert bloom), took a month off in Colorado with family, then resumed at the northern terminus to hike the remainder south. It worked out pretty well, putting me in a position to complete the Arizona Trail SOBO that same fall. As such, I still managed to walk from Canada to Mexico in one go, just not all the way along the CDT.

More than any other trail before it, the CDT taught me the need to stay flexible and open to various options. It was a hard trail that didn’t bend easily to fit my plans, so it was better/easier to bend to it. Where once I touted that my grand achievements were “walking from Canada to Mexico”, the adventures in between were actually more important than the start and end points. Later, after I hiked routes like the Grand Enchantment and Mogollon Rim Trails, the staunch ideals of continuous hiking from one political border to another became even less important. These routes have pretty arbitrary start and end points, with lines that form weird letters of the alphabet. The irregular canyons and meandering ridges of the SW don’t care about tidy political borders and cardinal points…just take a look at the outline of the Hayduke route (hopefully my next adventure)! Maybe we should embrace nature’s paradoxes: wherein a river is both linear and bending, constantly changing, and not always continuously flowing. Compass directions don’t equate to fulfillment, they’re only a means by which to navigate amazing outdoor spaces. I could wax on but hopefully this long-winded introduction is enough to give some perspective. I’m only trying to help readers be more open and informed in considering variations in their thru-hikes. Take it or leave it, just do whatever works best for you, not just what everyone else is doing!

What is a Flip-Flop?

I have no idea of its origins, but flip-flopping is basically thru-hiker-jargon for describing non-standard travel on a long trail. I’m hard pressed to say how it differs from section-hiking, since it’s essentially putting 2 or more long sections together to complete most or all of a trail. There are a myriad of ways to employ a flip-flop. Conventionally, it’s done by starting at a mid-point, hiking to one end, then resuming at the mid-point to hike to the other end. This is typically done in continuous progression, only stopping for a few days of travel to reset. This is the plan I followed and will be describing in detail for the PNT.

But really, a flip-flop is whatever you make of it, within the confines of weather, permits and trail conditions. A flip-flop can be initiated at the mid-point, a state border, or the division of 2 ecotones (high desert versus mountainous sections like those found on the PCT and CDT). Also, the direction of the hike can be switched mid-way through, multiple times, or kept the same (i.e. going NOBO on the AT from Harper’s Ferry to Katahdin, then Springer to Harper’s Ferry). And as I did on the CDT, sections can be hiked with time off in between. It just depends on the goal of the flip-flip, such as avoiding snow, crowds, bugs, mud, or heat. Perhaps a hiker simply needs to attend a wedding or graduation. With so many possibilities, many advantages and opportunities also come to mind.

Consider an AT flip-flop: there’s easy access to many parts of the trail but especially the mid-point at Harper’s Ferry (train from DC), the ever-increasing problem of overcrowding at the southern terminus can be avoided, and depending on timing, decent weather and conditions can be enjoyed throughout much of the hike. Better still, an inexperienced thru-hiker can start in the easier mid-Atlantic section, allowing them to build their trail legs more gradually and avoid injury. There are so many options and advantages that the ATC dedicates a whole page to the topic here. The AT is perhaps the most aptly-suited trail for flip-flopping, while other trails like the PCT don’t have as obvious of benefits or options…though still plenty of people have done so for the purposes of snow or fire avoidance (see the PCTA page on flip-flopping here).

How and why does a flip-flop of the PNT work?

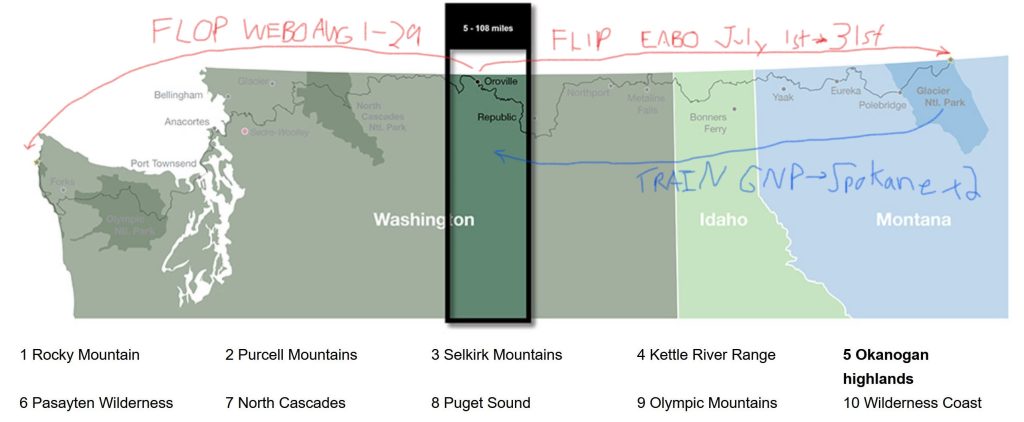

From my own experience, I think the PNT is one of those rare trails that’s perhaps better to flip-flop, rather than tackle as a continuous westbound or eastbound thru-hike. This has a lot to do with the nature of its east-west corridor along the Canadian border, resulting in a shorter weather window and no seasonal advantage as it applies to differences in latitude found on north-south trails like the PCT. Further, the major mountain ranges that can hold snow well into June/July are interspersed at pretty regular intervals along the trail. These are the Olympic Mountains, Mt Baker Wilderness (Swift Creek), North Cascades / Pasayten Wilderness, Selkirk mountains, Whitefish mountains, and Glacier National Park.

There are a few shorter snowy stretches worth mentioning, namely Copper Butte in the Kettle Range, Abercrombie Mountain west of Metaline Falls, and areas around Rock Candy Mountain and Northwest Peak…all spots that are relatively low-risk and could probably be handled in less than a day, as opposed to days to a week. I highlighted all these areas on the map below. Notably, the Rockies and Olympics bookend both PNT termini, barring any clear advantage for going WEBO or EABO in order to avoid snow. With closer study, a longer snow-less section from Oroville to Priest Lake should stand out. This was the section that my PNT flip-flop took advantage of, delaying my entry into snowbound parts by several weeks, which was just the break I needed for the melt.

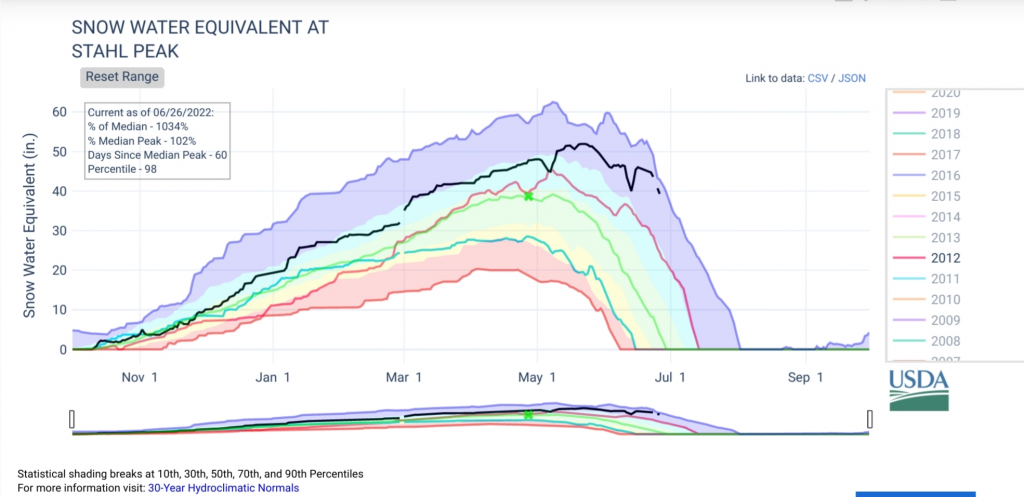

Why not just tough it out in the snow for a few weeks? This was my plan. I even had my ice axe and microspikes shipped to East Glacier, ready to do battle. Yet with further research and following the progress of early-season hikers, there were just too many factors tipping the scale from ‘toughing it out’ to ‘possibly dying’. The double whammy of GNP and the Whitefish at the beginning of the eastern PNT (both ranges also filled with Grizzly bears, BTW!) is tough, even without snow. The section is analogous to the CDT’s San Juans… if the first stretch of mountains don’t take it out of you, the next probably will…hence the popularity of the Creede cut-off. There was also this bit of data…

The Whitefish have perhaps the most consistently high and difficult ridges holding snow of any mountain section on the PNT. In 2022, a mid-June hiker made it over Stoney Indian and Brown Passes in GNP (after more than a dozen self-reported self-arrests!), only to have to bail halfway through the Whitefish. They also had to cross a lot of sketchy streams and washouts. Their experience sounded rather harrowing and I wanted no part of it. I considered road-walking around the Whitefish and/or delaying my hike by several weeks. But I hated to waste time and money and still potentially miss beautiful sections of the trail. In hindsight, had I waited a few weeks, I might have gotten stuck behind the fires that sprang up in the Cascades in mid-August. I’m very grateful to Buck30 and Steady for giving me the idea to flip-flop. They are the ones who researched the travel logistics and I owe them many thanks for a successful thru-hike!

My observations/experiences of a PNT flip-flop are based on one simple plan: 1. Start near the PNT mid-point of Oroville to travel EABO towards Glacier National Park. 2. Reach the eastern terminus to backtrack to the mid-point and finish the other half WEBO. Initially, my only objective was to avoid snow, and for these same reasons, such a plan would most likely work for getting an earlier-season start…perhaps beginning to mid-June. I haven’t put much thought into other flip-flop variations for the PNT, such that might be required to avoid fires closures. The whole point of an early start is to hopefully negate the need for that kind of shuffling. This will become more and more crucial with each passing year, as we see how climate change is already wreaking havoc on other trails like the PCT and Arizona Trail. But there were many other benefits to flip-flopping that I discovered during the course of my PNT thru-hike.

Benefits of a PNT flip-flop:

- There are relatively easy travel logistics in getting to or close to the mid-point of the PNT (covered in detail later). The mid-point trailhead at Whistler Canyon also has the best trail kiosk and register of the whole trail.

- I got an earlier start by putting off snowbound sections like GNP and the Whitefish Mountains, also…

- An earlier start through some of the most notoriously hot and dry sections (Okanogan highlands and hills around Republic) may result in more ideal conditions. This panned out great for me, with a few days of rain, temps in the 50’s – 70’s, and flowing springs everywhere. This made the stretch from Oroville to Metaline Falls wet and lush, rather than a dust-choked shuffle in 100 degree temperatures.

- An earlier start may result in fewer or no fire woes down the line… this is perhaps the most important reason for a flip-flip. Not only was I lucky to avoid fire closures, I was blessed with perfect visibility for my entire hike. Only after I returned to climb Mt Baker did I realize how good I had it. The fires in the Cascades had sprung up by then and I could barely see any of the surrounding mountains. This was in stark contrast to being able to see Mt Baker over a 20 day time span while I hiked the PNT. Of course there are never any guarantees that fires won’t affect your hike regardless of what you do, but you can certainly study past trends to see when fires are usually most active in the PNW (i.e. mid to late August).

- I was able to get a large part of the notoriously monotonous road walking out of the way early on, at a time when it was simultaneously nice do easy and mild miles while building my trail legs.

- I was able to put off worries about grizzly bears until later. Rather then needing to carry bear spray/canister, ice axe and microspikes (as I would have needed heading into GNP), my pack was very light without all these things. I picked up bear spray heading out of Republic but never needed my axe or spikes.

- I found that going EABO through the Selkirk’s Lions Head bushwhack section made the ridge route somewhat easier (see previous blog post PNT Route Options). I loved this route…it ended up being one of my best days!

- It’s so much easier going down the Parker Ridge, Selkirks Range, than going up. This is one of the biggest changes in elevation along the PNT. The Parker Ridge rises over 5000 feet from the Kootenai valley (Bonner’s Ferry), much of which is through a hot and exposed fire area. There’s a 10 mile dry stretch, to boot. WEBO’s (loaded up with water and many days of food) usually describe the climb as brutal. I could certainly see why as I was gliding down it. The descent seemed to go on forever. It’s equally nice going down from Webb peak, heading into the valley where Eureka sits.

- Heading EABO through Glacier National Park later in the season has multiple benefits:

- I found it very easy to get walk-in permits in Polebridge, which is directly along the route, as opposed to going out of the way to get permits from Two Medicine via East Glacier or from West Glacier.

- My timing avoided peak CDT SOBO/NOBO seasons, who compete for many of the same campsites on the eastern side of the park. In general, I found the backcountry to be pretty quiet at the end of July, which surprised me. I got all the campsites I wanted in my first try.

- I was able to take the Kintla Lake and Boulder Pass alternate, which was my favorite part of the park, so far. In fact, I think it’s worth doing a flip-flop just for this one benefit. The pass is amazing and not something that’s often an option for WEBO’s starting the trail in late June or even early July. See my PNT Route Options about this fantastic alternate.

- Visiting the park in late July allowed more flexibility throughout the park (routes like the Ptarmigan tunnel were open), plus made for a stress-free experience not having to worry about much or any snow. The weather, wildflowers, and waterfalls were simply glorious! This is one of the best parts of the PNT, so it was nice to enjoy it at its best!

- I got a lot of satisfaction in distributing most of the greatest backcountry sections into the latter part of my thru-hike: GNP, immediately followed by the Pasayten and Cascades, Mt Baker, and the Olympic Peninsula…all these together felt like my reward at the end.

- I enjoyed the solitude! The PNT is still a fairly quiet trail, so flip-flopping to avoid crowds is probably not necessary. However, doing so will almost ensure that you won’t be in a bubble…at least not in the beginning. I didn’t see any hikers for the first 5 days. Eventually I ran into some of the WEBO’s, but surprisingly very few given all the alternates and road walks. I made it back to Oroville just in time to join up with the front bubble of about 10 hikers. It was really fun hiking with them at intervals, but still very quiet most days.

I may be a little biased, but I actually had a hard time coming up with any cons to a PNT flip-flop. Here’s the best I could do:

- Flip-flopping is a more solitary experience, at least in the beginning and perhaps the whole way if you end up well ahead of everyone else. This can be an advantage or a disadvantage, depending on your outlook.

- An early EABO hiker will likely encounter a lot of blowdowns in the Kettle Range and possibly some near Abercrombie, the Shedroofs, and Selkirks. This is a problem common to any early start on the trail (you’d hit them in GNP and the Whitefish going WEBO), and just depends on your timing and how soon the trail crews are able to get out there. I was very lucky, having only one bad section in the Kettle Range. My timing seemed almost miraculous, such that trail crews cleared areas just days before I arrived each section and also just as the snow had melted… like a line of dominoes falling before me. This makes sense, since trail crews also have to wait for the snow to melt. No matter what you do, expect to hit terrible blowdowns in the Pasayten. It seems like the only options are go through them or get shut out of the area entirely due to fires later in the season.

- Flip-flopping is marginally more expensive because of additional travel costs. It doesn’t have to be this way if you plan a flip-flop from the very start (by flying into Spokane). It was more expensive for me only because I initially planned to start at the eastern terminus, thus had already made arrangements to arrive in Kalispell. The 2 train rides cost just over $110, so altogether probably $150 extra total…not too much of a hardship.

- EABO’s may be too uncertain about their arrival date to make online GNP permits ahead of time, having to rely on walk-in permits instead. WEBOs have to deal with a great deal of uncertainty as well, such as lingering snow, campsites still being closed, and bridges not being installed. I didn’t make advanced permits before my planned WEBO departure either, then was glad I didn’t. I think the online permit system for GNP is a bit of a mess and a rip-off. I stressed over the GNP permits and in the end, they were easier than getting permits for ONP and NCNP.

- I encountered a rattlesnake on the very first day, as I was climbing out of the Okanogan valley. It was the only one I saw the whole trip and it gave me a decent warning, thank goodness. What an ironic way to start the PNT. But I’d rather run into a rattlesnake than a grizzly first day out…at least I’m used to them after hiking in the desert SW and Florida.

- A flip-flop (or EABO thru-hike) is contrary to Ron Strictland’s (father of the PNT) vision of a water droplet’s path, flowing continuously from the Continental Divide to the Pacific Ocean. I touched upon some of the romanticized ideals of thru-hiking in my intro but didn’t address this one specifically, worried it might hit a few nerves. Not surprisingly, this was one of the very first comments my flip-flop post elicited on the FB page, so I decided to add some of my own thoughts about this at the very end. (Spoiler alert: the only water droplets actually following the path of the PNT are those carried in hikers’ water bottles, so this is not really a justified reason in discounting the idea of a flip-flop or EABO hike).

PNT flip-flop travel logistics and strategies:

Airplane and Train travel to Spokane (Wenatchee): The travel logistics of a flip-flop are fairly easy, thanks to the Amtrak Empire Builder train route. This train makes stops in East Glacier, West Glacier, and Whitefish, which are easily accessed from parts of Glacier National Park and/or Kalispell (the only major airport serving GNP). At least one leg on this train will probably be required for a flip-flip, and in my case it involved 2, since I flew to Kalispell based on my initial plan to start from Chief Mountain. Departing from both Whitefish and East Glacier, I found Spokane to be the easiest and cheapest destination: around $55 for a one-way ticket. Unfortunately, the train arrived Spokane in the middle of the night (2-4 am depending on how late it’s running), so I had 2 rather restless nights and hung out in the station for some uncomfortable hours. It wasn’t worth trying to find a hotel mid-morning, plus it’s impossible to know just how late the train will be running on any given day. At least it’s somewhat possible to get sleep on the roughly 6 hr train ride.

There’s an option to go one stop further on the train to Wenatchee, where according to Google, one can take a series of buses all the way to Oroville. In my case, adding this one stop would have cost triple the amount: $150 for a one-way train ticket, so I didn’t think it was worth it. Perhaps if coming the opposite direction from Seattle, stopping in Wenatchee would make better sense and be more cost effective…do consider this if you are starting your trip from the west coast. But it you are a planning a flip-flop from the onset, probably the best (cheapest and easiest) option is to fly directly to Spokane.

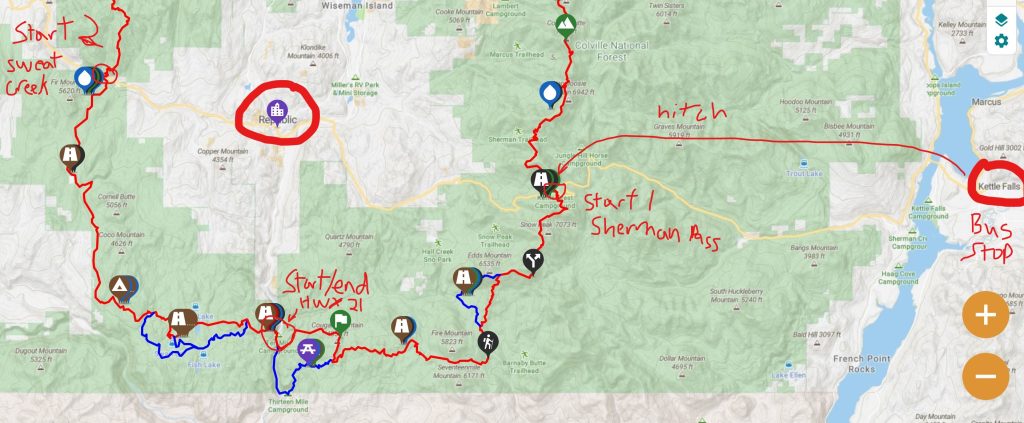

From Spokane to Kettle Falls, Republic or Oroville: On my first go-around, I got really lucky finding a ride all the way from Spokane to Oroville, utilizing the PNT Facebook page. However, once I committed to starting near Oroville, I was committed to getting back there a second time. My FB pandering didn’t pan out on round 2, so my friend and I just hitched the whole way (about 180 miles, which took 5 different rides and more than half the day, even though we never waited more than 15 minutes for each ride). We took a city bus to get to the outskirts of Spokane and were two women with great hitching luck…your result may vary.

Our fall-back option was to take the Gold Line bus from Spokane to Kettle Falls, which runs north twice daily and costs around $20 for a one-way trip. From Kettle Falls, it should be a pretty easy hitch over Sherman Pass to Republic. Again, the FB page can be your friend here and I’d suggest contacting one of the many trail angels in Republic to inquire if they might be able to offer a ride. You don’t even need to make it all the way to Oroville or even Republic if you decide to start the trail right from Sherman Pass, roughly 30 miles west of Kettle Falls and along the way. From there, it’s easy to take advantage of the trail horseshoe that encompasses Republic (see map below).

This nice thing about starting the PNT around Republic is that there are so many options (plus it’s one of my Top Favorite Trail Towns and full of Trail Angels!). A fresh-out-of-the-gate hiker can really tailor their plans to do 1 or 2 sections, divvying up both the miles and direction of travel between resupply to suit their needs. Had I not gotten the ride to Oroville the first time, I was considering the following plan: start at Sherman Pass, hike south/WEBO on the trail about 60 miles to the Sweat Creek Trailhead west of Republic, hitch to Republic for resupply then back to Sherman Pass to resume the trail heading EABO to GNP. On my return to Republic, I would have picked up the trail WEBO from Sweat Creek. Since I was already flip-flopping, what did it matter if I added a smaller flip-flop? In fact, I did do a modified version of this plan when I got to Republic, taking advantage of ride offers to Sherman Pass and a net elevation loss of 5k’ from the pass to HWY 21 (see PNT Day 5).

Despite the potentially more costly/complicated logistics of getting to Oroville, I will say that it was nice to start my flip-flop there. Being the official halfway point of the PNT makes it a logical, easily-explained, and aesthetically-pleasing option. It’s only roughly 60 more miles from Republic to Oroville, but the segment involved quite a bit of road walking, especially with the Mt. Bonaparte fire detour still in effect. It’s all the more advantageous to get this road walking done while it’s still relative cool in early summer (70-80 degrees as opposed to over 100 by the time I returned a month later!). Additionally, there’s a nice trail head sign and Thunderbird at Whistler Canyon, plus the flashest PNT Informational Board of the whole trail, complete with trail register! You’ll find nothing of the sort at either of the official PNT termini, perhaps evidence that the PNT is meant for flip-floppers?

Some additional ideas for a really early start and/or other sections that can be hiked early-season:

If taking more of a section-hike approach, one could knock out a few low-elevation parts like the Olympic Coast and Puget Sound.

- Fly into Seattle, take public transportation (bus/ferry) to Admiralty Head on Whidbey Island to begin a section hike through the Puget Sound, all the way to Sedro-Woolley, or perhaps even as far as the Mt. Baker & Baker Lake area. Bell Pass on the south shoulder of Mt Baker will likely be a snowy show-stopper in June. If not, Swift Creek north of Baker Lake will probably not be safe to ford until as late as July. From the ferry crossing on Whidbey Island to HWY 9 or Lyman is a distance of about 100 -115 miles that can be done in nearly any season and either direction. There’s public transportation to/from Sedro-Woolley to points north and south of the I-5 corridor. The biggest downsides of this plan are potentially missing out on the Trail Angel experience in that area, plus ripe blackberries along the roads (typically mid to late August).

- Another section hike in the area is the Olympic coast, Forks / Cape Alava…roughly 60 miles. I really don’t recommend this, because I think it’s important to tie in the Olympic mountains with the coast…all part of an inter-connected and beautiful ecosystem. As such, I found greater meaning in journeying through the Olympic peninsula together as a whole. Plus, finishing at the coast is hard to beat, it’s just so amazing and unique.

- After doing a section or two on the western end, take the train from Seattle to Wenatchee or Spokane and follow the guidelines above. You’ll have a big head-start on the trail, with over 100 miles and a lot of road-walking under your belt.

More Flilosophy: Should the vision of a water droplet flowing from the Continental Divide to the Pacific Ocean determine which way to hike the PNT?

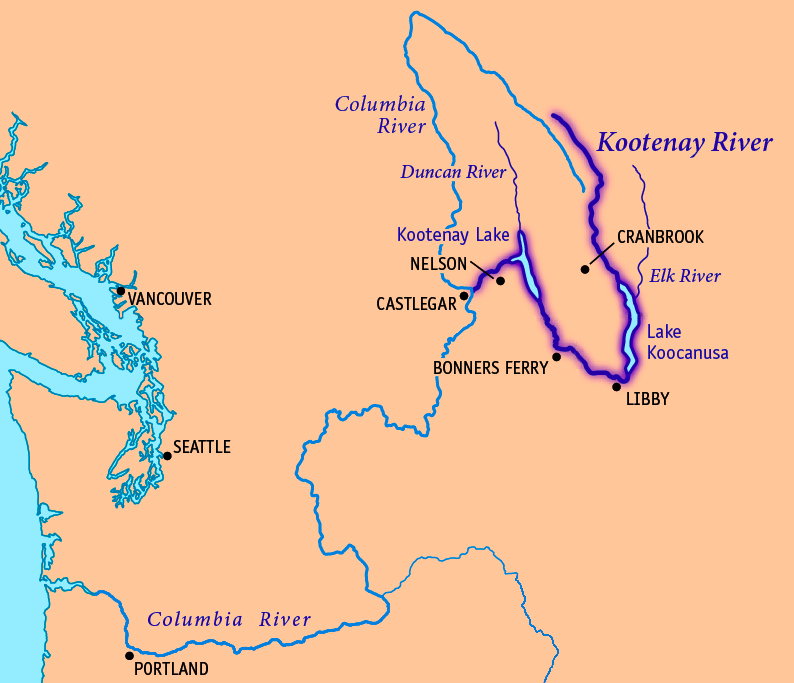

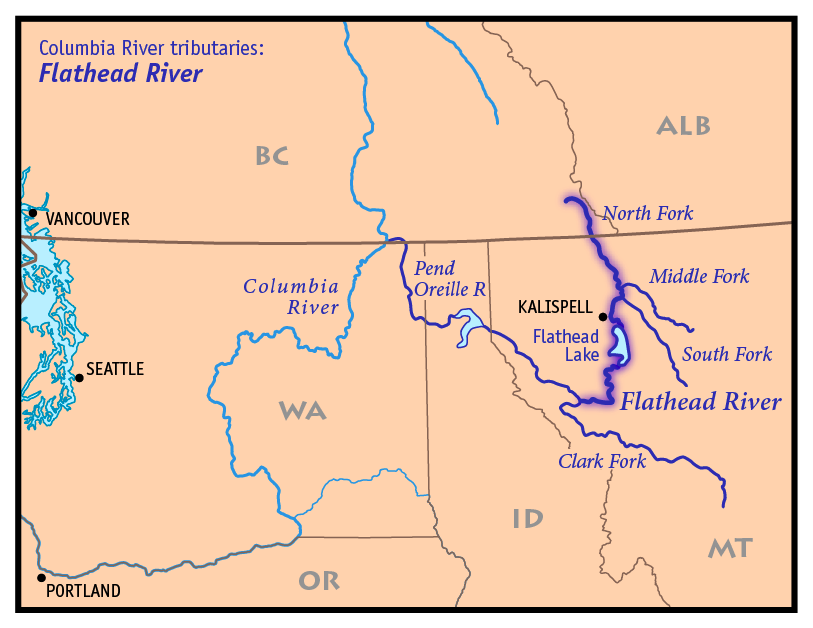

In admitting that the PNT is itself a man-made idea and project, this vision is essentially a romanticized marketing tactic that only very loosely represents the actual path of the PNT. No water droplet would ever defy gravity to go up and over all the mountain ranges that bisect the route. Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad it’s served in garnering support for the PNT’s National Scenic Trail designation and drumming up interest from hikers, trail maintainers, and donors. It certainly appealed to me. But it need not have any bearing on decisions about hiking direction and/or where to start the trail because it’s not based in geographical or hydrological reality. Take a look at the maps above to see several of the major watersheds in the region. The Kootenai river flows south near Eureka (Lake Koocanusa), then takes a big U-turn to go north past Bonner’s Ferry and back into Canada. There it again U-turns to join the Columbia, wagging throughout Washington and eventually west, forming the border with Oregon. The Flathead also flows south past Polebridge then takes a huge U-turn to flow north, becoming the Pend Orielle and flowing north past Metaline Falls. It too joins the Columbia River in Canada, only to flow south again.

None of these watersheds even remotely follow a semi-straight trajectory along the Canadian Border. Which is not to say they aren’t still a defining element in the overall experience of the PNT. Crossing so many mountain ranges and the immense river valleys in between them is actually one of the most unique and amazing features of the PNT. It’s equally exciting to cross the same rivers several times, hundreds of miles apart. Effectively, the Kootenai is crossed a total of 3 times (once after it’s joined the Columbia River). In 2 instances, it’s flowing south yet in the middle it flows north. It meanders all over the place, switching things up to follow a path of least resistance…kind of like some of the ideals of a flip-flop!

‘Going against the flow’ of the water path vision was something I initially struggled with, since I identified with this vision as almost an analogy of my own life journey. I grew up in a land-locked state (Colorado) but left at age 17 to answer the call of the sea. I joined the Coast Guard and later spent most of my career as a marine biologist and officer/mate of research vessels. Thus, replicating my journey from the mountains to the sea in a thru-hike really appealed to me. As I found myself heading east from Oroville in the ‘wrong’ direction, I wondered if this incongruity might result in my thru-hike feeling less meaningful.

After multiple 5-7 thousand foot ascents and decents over the huge mountain ranges, I quickly realized that the water path vision was just a poor analogy that need not detract from my enjoyment of the trail. Given my nautical background, I came up with a different aquatic analogy for the PNT. I began to think of myself as a navigator of a sea of mountains, going over the crest of huge waves and swells, down into the troughs, then back up again. Over and Over. Some days were very rough, others smooth sailing. Then one day I came to the shores of the Pacific Ocean and it was everything I’d ever hoped it would be. True to it’s name, the surface was placid and flat, providing a wonderful contrast to the tumultuous mountains. And most importantly, having walked all of the PNT to arrive at the ocean still held the meaning that I hoped it would.

Deep snow and trail closing fires. I experienced both on my CDT NOBO hike, and even though I did leave a continuous footfall, I was not overly pleased with the results–so much so, that I hiked those “missed” sections to see what I missed. A Flip-flopping plan may have been more ideal.

I had “perfect” timing on my WEBO PNT hike in 22. I didn’t need spikes or axe in GNP and I was just ahead of fire closures further west–very lucky. It’s good for hiking community that you expressed your logistics and reasoning. Seems highly logical to flip-flop on PNT. THANKS!